The Family Health Care Institute’s bulletin (a part of the King Hussein Foundation institutes), today, Wednesday, offers important information about Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (Khaberni - PCOS), which is considered one of the most widespread hormonal and metabolic disorders among women of reproductive age, with global rates ranging between 8% and 13% according to the diagnostic criteria used.

The bulletin provides readers with the mechanisms of the disease in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, the clinical symptoms and signs, the criteria used in the diagnostic process, the treatment methods, and the necessity of long-term follow-up.

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome represents a multifaceted condition encompassing reproductive, metabolic, and dermatological manifestations, making it a significant health issue extending beyond the scope of reproductive health. Despite numerous studies, the exact cause of the syndrome remains unclear, but it is considered a result of a complex interplay between genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors.

Disease Mechanisms (Physiopathology)

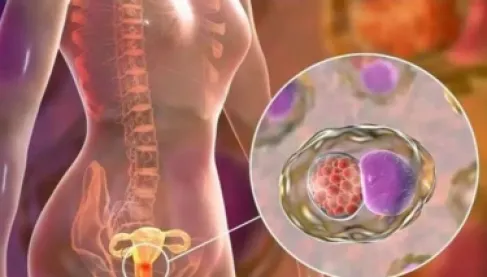

The disease mechanisms in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome revolve around a dysfunction in hormonal regulation, particularly in the hypothalamus-pituitary-ovary axis, in addition to insulin resistance and increased androgen production in the ovaries. Patients often exhibit elevated luteinizing hormone (LH) levels compared to follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), leading to increased activity of specific cells in the ovary and more androgen production. Androgen excess contributes to symptoms like hirsutism, acne, and male-pattern hair loss.

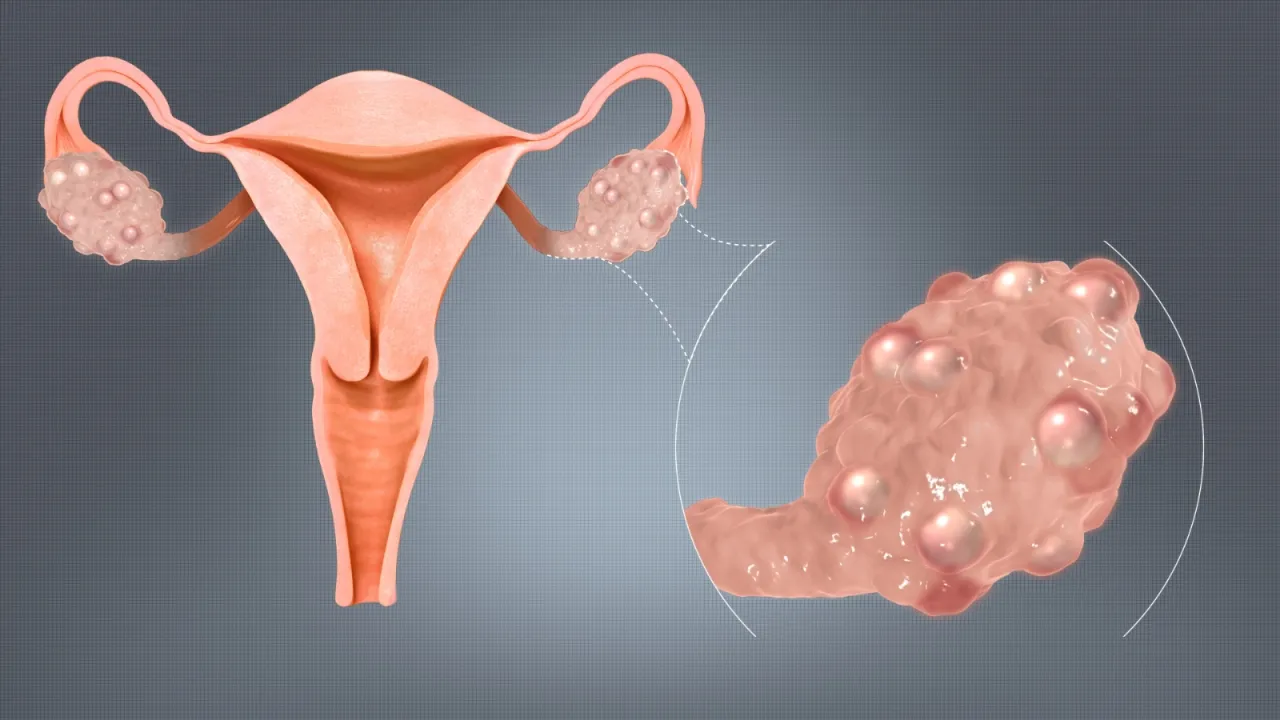

Insulin resistance is a main feature in a significant percentage of cases, even among women with normal weight. Compensatory hyperinsulinemia leads to increased androgen production and reduction in sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) synthesis, which increases free androgen levels in the blood. This hormonal imbalance hinders follicle maturation, resulting in poor ovulation and the formation of many small, immature follicles, giving the ovaries a polycystic appearance through ultrasonography.

Genetics also plays a clear role, as the syndrome's prevalence is noted among family members. Lifestyle factors such as obesity, physical inactivity, and dietary habits exacerbate insulin resistance and diversify the clinical picture of the disease.

Clinical Symptoms and Signs

Symptoms of the syndrome generally start shortly after puberty, although diagnosis may be delayed for years due to varying symptom severity. Symptoms encompass three main aspects: reproductive, metabolic, and dermatological.

Reproductive symptoms include menstrual cycle irregularities, delayed or absent menstruation, heavy periods, and delayed pregnancy or infertility. Many women first seek medical advice for difficulty in conceiving. Hyperandrogenism manifestations include hirsutism, acne, and hair loss, symptoms that can cause psychological stress and affect quality of life.

The metabolic aspect includes insulin resistance, which increases the likelihood of glucose intolerance and may cause type 2 diabetes, elevated lipids, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. The syndrome is also associated with weight gain, particularly central obesity in the abdominal area, exacerbating metabolic disturbances. Long-term risks of cardiovascular diseases increase.

Psychiatric disorders such as anxiety, depression, and eating disorders are prevalent among those affected by the syndrome, underscoring the importance of a comprehensive therapeutic approach.

Diagnosis

Rotterdam criteria are widely used for diagnosing the syndrome, requiring two of the following three criteria after excluding other causes:

1 - Poor ovulation or its cessation (menstrual cycle disturbance).

2 - Clinical or laboratory signs of hyperandrogenism like elevated levels, hirsutism, or acne.

3 - Polycystic ovarian appearance through ultrasonography.

Laboratory tests include total and free testosterone levels, DHEA-S, SHBG, fasting glucose, insulin, and lipids. Tests are also conducted to exclude thyroid disorders, hyperprolactinemia, or congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

Ultrasonography serves as a supportive tool but is not mandatory for diagnosis if the other two criteria are met.

Treatment

Treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome depends on an individual and integrated approach considering the patient's symptoms, reproductive goals, and metabolic state. Treatment can be categorized into three groups: lifestyle modification, pharmaceutical treatment, and treatment for delayed conceiving.

Lifestyle modification is the cornerstone, especially for those with excess weight. Losing 5–10% of weight significantly improves menstrual cycles, insulin sensitivity, and ovulation function. A balanced diet and regular aerobic and resistance exercises are recommended.

Pharmaceutical treatment focuses on symptoms. Combined birth control pills are the first treatment for regulating menstrual cycles, reducing androgens, and improving acne and hirsutism. Anti-androgens such as spironolactone may be added if necessary.

Metformin is used to improve insulin resistance and regulate the cycle, especially if there is a metabolic imbalance. Topical options are available for treating acne and hirsutism.

If pregnancy is desired, the doctor may resort to ovulation induction, with letrozole currently the preferred option due to its higher success rate compared to clomiphene. In vitro fertilization may be considered if necessary.

Long-term Follow-up

Given that the syndrome is a chronic condition, periodic follow-up is necessary to assess menstrual cycles, metabolic complications, weight, and mental health. Regular checks for diabetes, lipids, and cardiovascular risk factors are recommended.