Khaberni - In an era where smartphones never leave the hands of children and teenagers, access to shocking videos, horrifying images, and misleading information has become readily available to all age groups. Despite increasing warnings about the impact of this content on young people's mental health, most still spend long hours in front of screens.

The "Guardian" conducted an interview with seven experts in mental health and media about the best ways to talk to children about shocking and violent news, and how to protect them from misleading information, in addition to the appropriate age to start these discussions.

How do we start talking to children about bad news?

Journalist Anya Kamenetz and publisher of the "Golden Hour" newsletter emphasize the importance of asking children what they already know, correcting misconceptions, and involving them in seeking information from reliable sources.

Psychiatrist Eugene Beresin, Executive Director of the Clay Center for Young Healthy Minds at Massachusetts General Hospital, points out that children’s primary fears revolve around feeling safe and who cares for them, and it's important for parents to listen to these fears and reassure them.

What if children accidentally see shocking content?

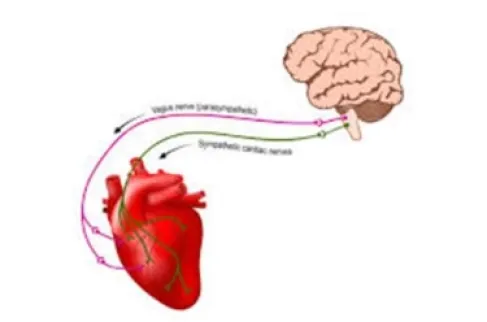

Psychologist Tori Cordiano notes that many teenagers unintentionally come across violent videos, which can cause them trauma that they don't express for fear of blame. She emphasizes the importance of opening safe communication channels, and explaining the risks of seeking such content and its lasting impact on the brain.

In the same context, Johns Hopkins University Professor Ashley Rogers Berner, author of "Building Better Citizens," calls for honesty with children when discussing events of political violence, stressing that these incidents are rare and that the law holds the perpetrators accountable.

How do we immunize our children against misleading information?

Writer Holly Kirby recommends teaching children critical thinking skills and verifying information before believing it, given the rapid spread of false news through social media platforms.

Cordiano encourages setting clear rules for smartphone use, such as banning devices in bedrooms at night and reducing app use at an early age.

What should be avoided?

Kamenetz warns against continuously playing news at home, especially for younger children, as they absorb anxiety without understanding the context.

Tara Conley, Assistant Professor of Media and Journalism at Kent State University, emphasizes avoiding claiming complete knowledge, because children realize that, and parents should practice humility and listening.

How do we reassure children amidst real concerns?

Conley suggests a simple and effective activity: writing supportive messages to children, helping them feel secure and belong. Cordiano emphasizes the importance of sticking to school safety drills and professional guidance without causing panic.

And what about the concerns of mothers and fathers themselves?

Kamenetz advises that parents take care of their own health first, and be a model for a balanced consumption of news, away from browsing before bedtime.

Conley encourages participation in volunteer activities that help enhance the sense of capability and control.

When do we begin this conversation?

Jill Murphy asserts that children are exposed to news at an early age, often from influencers online, so it is best to start discussions early with age-appropriate information.

Kamenetz, citing the example of the coronavirus pandemic, says that circumstances may impose the conversation, but correctly guiding the child remains key to maintaining their mental health.