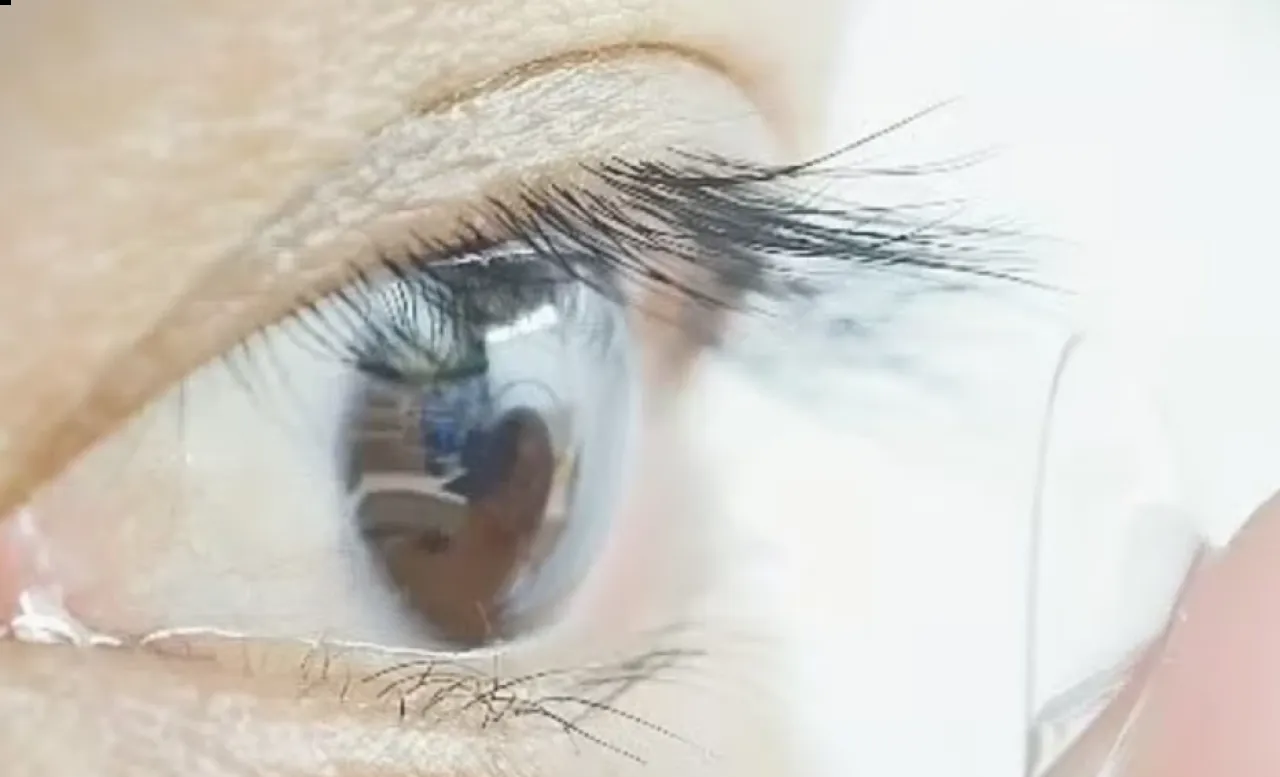

It may sound like something out of a modern science fiction film, but scientists have developed contact lenses that enable people to see in the dark. Unlike night vision goggles, these lenses do not require a power source and allow the wearer to perceive a wide range of infrared wavelengths.

These lenses, developed by a team from the University of Science and Technology in China, contain nanoparticles capable of converting invisible infrared light into visible wavelengths.

Interestingly, they work even when the eyes are closed, as infrared light penetrates eyelids more easily than regular light, reducing visual interference and enhancing clarity of vision, according to the "Daily Mail."

Seeing the Unseen

Normally, humans only see a narrow band of light ranging from 380 to 700 nanometers. However, the new lenses enable the perception of infrared rays in the range of 800 to 1600 nanometers, a light energy that represents more than half of the solar radiation, but was invisible to mammals.

Previously, the team demonstrated the possibility of enabling mice to see infrared by injecting nanoparticles into the retina, but they have now moved to a non-surgical solution by incorporating these particles into soft, flexible contact lenses.

Color-encoded Vision

Thanks to further development, the lenses are now able to encode different wavelengths of infrared into visible colors:

Light at 980 nanometers turns blue

Light at 808 nanometers turns green

Light at 1532 nanometers turns red

This allows wearers of the lenses to distinguish between light sources and details more accurately in the dark.

Promising Applications in Security and Medicine

According to Professor Tian Xue, the lead researcher in the study, this technology could be useful in areas such as security, transferring encrypted information, rescue missions, counterfeiting prevention, and potentially helping color-blind patients distinguish colors by converting certain wavelengths to visible ranges for them.

Currently, the lenses only detect infrared rays from LED sources, but researchers are working to enhance their sensitivity to detect weaker levels of radiation, and possibly integrate them with drugs or future therapeutic technologies.

The researchers wrote in the journal Cell, "These contact lenses represent a step toward wearable devices with high optical flexibility, opening a window to an unprecedented view of the electromagnetic spectrum, which has long been inaccessible to mammals."